JANUARY 15th, 2019

Radio, Radio!

I loved college radio. I won’t go so far as to say it saved my life, but it offered a welcome reprieve from the grip of undergraduate ennui, a debilitating condition that left me stunted and stoned somewhere between delayed adolescence and obliterated indifference.

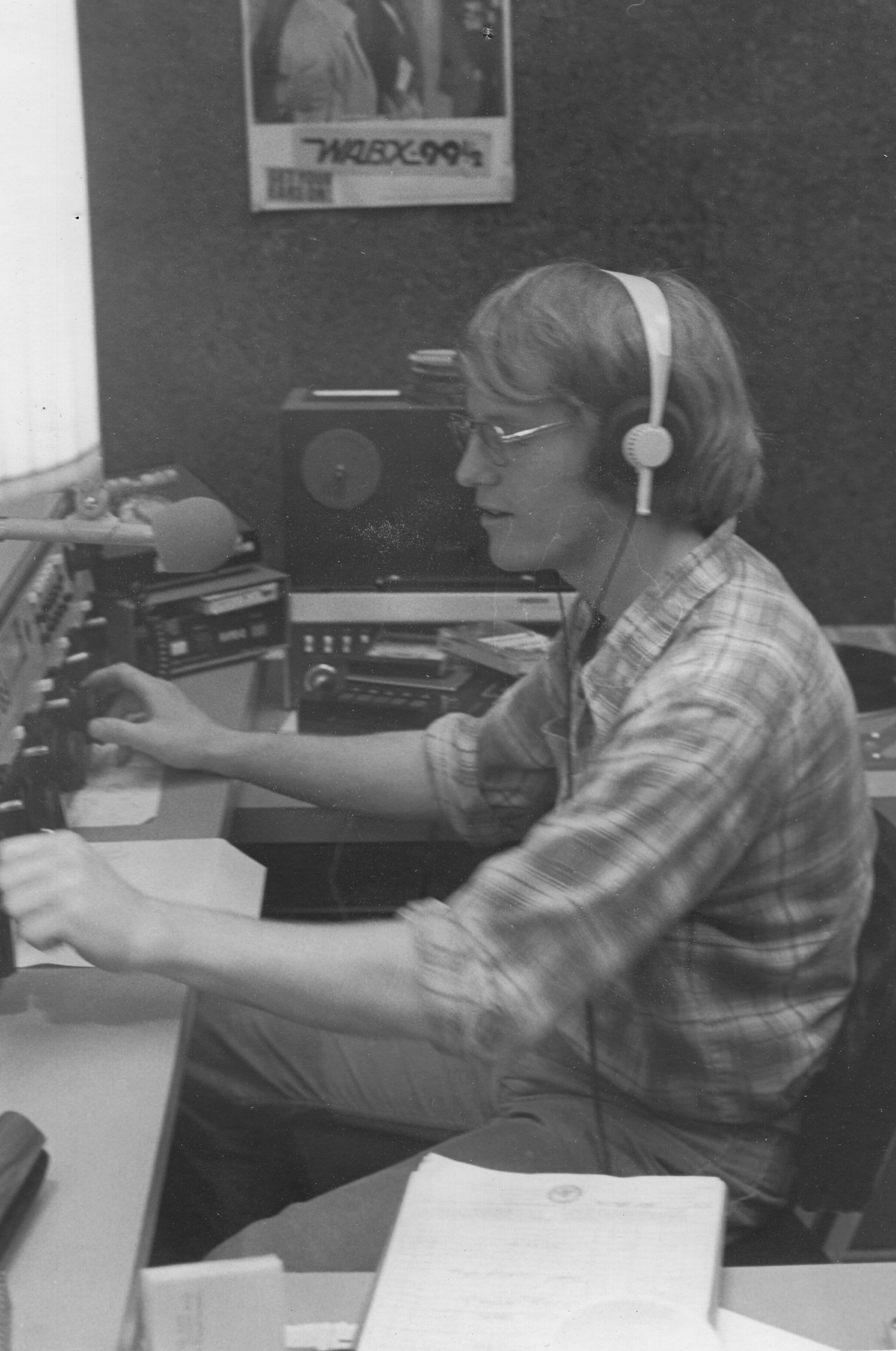

WLUC was one of three student-run radio stations that my university (remarkably) managed in the late 1970’s. Housed in a tired but cozy vintage two flat on the far edge of campus, it claimed no signage, no university staff, no campus security keeping an eye on the property, and in fact, gave no indication of occupancy of any kind let alone its functioning as a laboratory of higher learning. Only call letters scribbled on a weathered strip of masking tape above the broken doorbell served as proof of our residency.

I joined the station in 1979 at the height of a growing rift between DJ’s and station management, a divide that stemmed from two indisputable truths of the time: students despise being managed by other students; and the Eagles suck! (or not, depending on your place in the divide). As the station’s newly appointed music director, a position I later discovered no one else wanted as it required policing unruly on-air staff, I was naively honored, and sincerely shared in the belief that we, the station executives, were actually free-thinking airwave evangelists responsible for bringing the gospel of punk and new wave to the Foreigner-loving misguided masses, all while sticking a thumb in the eye of the corporate radio establishment (those suits are sucking the life out of rock n’ roll, man!).

The DJ’s held a more populist view: punk was for loser freaks and Van Halen ruled! And to make the point, they kidnapped the record library’s “texture” section – jazz and folk albums we insisted they sprinkle into the daily playlist, a programming mandate we thought would make us sound more, well, smart – and held hostage until they be allowed to play more Rush. Leading the protest was The Kid, “your jock down the block ready to rock” who ceremoniously prepped each show by donning sunglasses, a silk scarf, a splash of Aqua Velva, and one of a several tropical shirts he stuffed in a brief case and carried businesslike to and from the studio each and every day.

The fact that almost no one was listening (our signal reached only the student union and, oddly, the bursar’s office, where it played with abundant static) did not diminish the relevancy or passion of our standoff. The music mattered. Hell, it defined us. For some, it was all that separated us from a path to almost certain personal and professional conformity.

Our limited audience, however, did not in any way hinder the eager solicitation and deference we received from major record companies. College broadcasters held sway with label A&R reps because college audiences were quick to embrace new music and champion artists that nobody ever heard of. Whatever buying power we lacked we made up for in taste and an ear tuned for the next big band. Record label reps not only took our calls, they called us! And sent us records! For FREE, by the box load, mailed to our doorstep just for the asking. “Let me know what you think of that new Buzzcocks,” they’d ask in earnest. I can tell you right now, I LOVE IT. And yeah, I’ll most definitely give it a listen, too.

All this anointed credibility spurred in us no shortage of youthful audacity. The telegrams we sent (phone calls or letters wouldn’t adequately convey the legitimacy of our interest) inviting John Lennon, David Geffen and Talking Heads to our annual student radio conference didn’t result in them actually attending, but they did respond! And may have even considered it. And that alone was cool.

Others did attend, however, and spoke and performed to rapt audiences of not mere fans, but young acolytes genuinely grateful for the life affirming inspiration. I still carry the yellowed and tattered business card remains of blues legend Willie Dixon in my wallet, because after all, “the blues is like the facts of life,” a lesson I can’t seem to learn often enough.

For me, then a self-conscious wallflower and devout worrywart, college radio wasn’t just an oasis from the inescapable growing pains of young adulthood and the fears of looming real world decision making, it’s where I dared for the first time to shed my anonymity. Through those unmarked doors and over those airwaves, we were all The Kid, trying on the clothes of our own choosing, and ultimately coming of age in the company of fellow misfits, closet exhibitionists and fledgling raconteurs whose friendship I enjoy to this day.

— Rich Moskal, Former Head of the Chicago Film Office

JANUARY 12th, 2019

It was the late 70’s in Nowheresville, America (aka Kalamazoo, Michigan). I was a d.j. on the college radio station, WIDR, when a revolutionary blast of music caught us in it’s tailspin. The Ramones, Sex Pistols, the Clash. These bands were tearing the roof off the music biz and it woke us out of our post-Vietnam torpor. We seized that stripped down, DIY music for our own and never looked back. Every generation claims it’s own music. For us, this was it. But there was plenty of tension between our younger, punk generation and the station’s old guard. At the beginning of the punk era we weren’t even allowed to play the Sex Pistols and the Clash for fear of obscenity. But, of course, we did it anyway. It was part of the punk ethos!

The seed for my film, “Waiting for the Clash,” was an outdoor concert we used to hold every spring called The Kite Flight (why? I don’t know). In 1980 I was the stage manager for that year’s concert. In February we started brainstorming about who we could get to be the headliner for the show. My best friend at the time, Dave, suddenly burst out, “What about U2? They’re playing their first U.S. tour this Spring!” Ludicrous as it sounds now, U2 at the time was not yet famous and college radio was the only outlet for punk and new wave music (and the record companies knew it). So we began negotiating with U2’s manager and it started to seem like it would happen. Then, suddenly, they backed out (can’t remember the excuse) and we settled, at the last minute, on Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels (well past their prime). Though devastating at the time when I reflected back on the story many years later I realized it had the makings a great comedy film. But I set the film in 1978 and turned U2 into the Clash and the rest is history.

— Bob Hercules, Co-Writer / Director